You might have fallen for someone’s attempt to disinform you about current events. But it’s not your fault.

Even the most well-intentioned news consumers can find today’s avalanche of political information difficult to navigate. With so much news available, many people consume media in an automatic, unconscious state – similar to knowing you drove home but not being able to recall the trip.

And that makes you more susceptible to accepting false claims.

But, as the 2020 elections near, you can develop habits to exert more conscious control over your news intake. I teach these strategies to students in a course on media literacy, helping people become more savvy news consumers in four simple steps.

1. Seek out your own political news

Like most people, you probably get a fair amount of your news from apps, sites and social media such as Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, Apple News and Google. You should change that.

These are technology companies – not news outlets. Their goal is to maximize the time you spend on their sites and apps, generating advertising revenue. To that end, their algorithms use your browsing history to show you news you’ll agree with and like, keeping you engaged for as long as possible.

That means instead of presenting you with the most important news of the day, social media feed you what they think will hold your attention. Most often, that is algorithmically filtered and may deliver politically biased information, outright falsehoods or material that you have seen before.

Instead, regularly visit trusted news apps and news websites directly. These organizations actually produce news, usually in the spirit of serving the public interest. There, you’ll see a more complete range of political information, not just content that’s been curated for you.

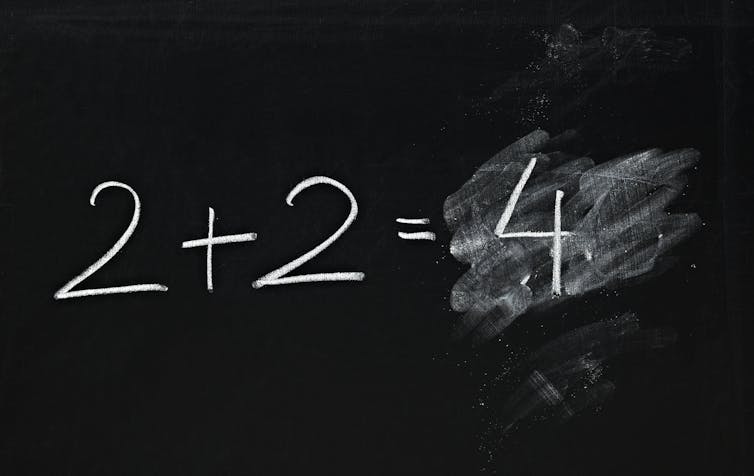

2. Use basic math

Untrustworthy news and political campaigns often use statistics to make bogus claims – rightfully assuming most readers won’t take the time to fact-check them.

Simple mathematical calculations, which scholars call Fermi estimates or rough guesstimates, can help you better spot falsified data.

For instance, a widely circulated meme falsely claimed 10,150 Americans were “killed by illegal immigrants” in 2018. On the surface, it’s hard to know how to verify or debunk that, but one way to start is to think about finding out how many total murders there were in the U.S. in 2018.

Murder statistics can be found in, among other places, the FBI’s statistics on violent crime. They estimate that in 2018 there were 16,214 murders in the U.S. If the meme’s figure were accurate, it would mean that nearly two-thirds of U.S. murders were committed by the “illegal immigrants” the meme alleged.

Next, find out how many people were living in the U.S. illegally. That group, most news reports and estimates suggest, numbers about 11 million men, women and children – which is only 3% of the country’s 330 million people.

Just 3% of people committed 60% of U.S. murders? With a tiny bit of research and quick math, you can see these numbers just don’t add up.

3. Beware of nonpolitical biases

News media are often accused of catering to people’s political biases, favoring either liberal or conservative points of view. But disinformation campaigns exploit less obvious cognitive biases as well. For example, humans are biased to underestimate costs or look for information that confirms what they already believe. One important bias of news audiences is a preference for simple soundbites, which often fail to capture the complexity of important problems. Research has found that intentionally fake news stories are more likely to use short, nontechnical and redundant language than accurate journalistic stories.

Also beware of the human tendency to believe what’s in front of your eyes. Video content is perceived as more trustworthy – even though deepfake videos can be very deceiving. Think critically about how you determine something is accurate. Seeing – and hearing – should not necessarily be believing. Treat video content with just as much skepticism as news text and memes, verifying any facts with news from a trusted source.

4. Think beyond the presidency

A final bias of news consumers and, as a result, news organizations has been a shift toward prioritizing national news at the expense of local and international issues. Leadership in the White House is certainly important, but national news is only one of four categories of information you need this election season.

Informed voters understand and connect issues across four levels: personal interests – like a local sports team or health care costs, news in their local communities, national politics and international affairs. Knowing a little in each of these areas better equips you to evaluate claims about all the others.

For example, better understanding trade negotiations with China could provide insight into why workers at a nearby manufacturing plant are picketing, which could subsequently affect the prices you pay for local goods and services.

Big businesses and powerful disinformation campaigns heavily influence the information you see, creating personal and convincing false narratives. It’s not your fault for getting duped, but being conscious of these processes can put you back in control.

Elizabeth Stoycheff, Associate Professor of Communication, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.